Local women now use high-tech mobility

Two researchers outfitted a fishing community in the mangrove forests of Colombia with Torqeedo electric motors. The local women now use high-tech mobility to collect cockles in the swamps. How does that change their way of life? Can they protect the environment and improve their standard of living at the same time?

The first time Gordon Wilmsmeier and Stefan Sorge travelled to the Colombian mangrove swamps with an electric outboard, the local inhabitants thought they were crazy. At least, that’s how the two researchers remember it. Men and women, young and old, gathered around the German visitors to take a look at the strange object they had brought along. The locals wondered if they were serious about navigating the swamps with an electric motor. This thing looks like a fan, maybe a computer. And it doesn’t make any noise? Will it have enough power?

Wilmsmeier and Sorge were trying to find a way for people in poor, remote, and ecologically sensitive regions to make a sustainable living. Could you protect the environment and improve the standard of living at the same time? How would you get the local population involved in creating new solution.

Gordon Wilmsmeier is a professor of logistics at the University of Bogotá. Stefan Sorge describes himself as a “mixture of a sociologist and an economist” and works at the University of Applied Sciences in Berlin. The two first met in a bar in Santiago de Chile. What started out as a casual acquaintance has given birth to the internationally renowned development project Inno Piangua. In addition to the universities the two academics work for, political institutions including Colombia’s national fisheries association and NGOs such as the WWF are participating.

Paradise? It depends on who you ask

Colombia’s Pacific coast is home to one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet. Over 300 native bird species populate the area around the village of Guapi, where Inno Piangua is working. For a conservationist, it sounds like paradise, but the people here face poverty and high rates of drug crime. Electricity service to their stilt homes is limited to a few hours a day because high fuel transport costs make the village’s old, inefficient diesel generators too expensive to run. Mobile phone reception and internet connectivity are limited or non-existent. “Lots of innovations never make it out here,” Wilmsmeier explains.

The women use the electric boats to collect Piangua, a variety of cockles that lives among the mangroves here.

Most people here earn their livelihoods from fishing, casting their nets into the Guapi River and its tributaries or harvesting piangua, a mollusc which lives in the tidal mudflats and mangrove forests. Their boats are powered by gasoline engines, but fuel is so expensive that it is difficult to earn a living, and the motorboats pollute the very environment that provides the catch. Maybe highly efficient electric outboard motors could help, the scientists thought. So, they contacted Torqeedo.

“We were so impressed with their dedication,” says Lukas Timcke, himself a native of Colombia and the South America coordinator at Torqeedo. The company has supported many development projects in the region. In one nearby example, Torqeedo supplied the motor for a solar-powered boat that now ferries schoolchildren on the Ecuadorian Amazon. “We think it’s important to foster sustainable international development work,” says Timcke. “But we’re no NGO. We want to stay a step ahead of the competition and discover new business models, too.”

Veuillez ajuster vos paramètres de cookies en utilisant le bouton ci-dessous

et activer les "Cookies fonctionnels".

Veuillez ajuster vos paramètres de cookies en utilisant le bouton ci-dessous

et activer les "Cookies fonctionnels".

Veuillez ajuster vos paramètres de cookies en utilisant le bouton ci-dessous

et activer les "Cookies fonctionnels".

Nature and the future—Torqeedo electric motors in action on the Colombian Guapi River.

Torqeedo donated five Travel 1003 and Cruise 2.0 electric outboards to the project. In May, 2018, the first motors arrived in the village. Two years later, four of the new motors are being used daily, while one stays in Bogotá as a backup. The local gas station attendant sees where things are headed. He is thinking about training to become an electrician.

“Just install it and go!”

How did the academics overcome the initial scepticism of the locals? Wilmsmeier says the key was giving them an opportunity to experience the motors right away. “We said, ‘Here, take this with you, install it on your boat, take it out for a ride.’ We didn’t lecture them on a million things they should or shouldn’t do. They got to figure it out for themselves.” The anglers found the electric motors were easy to install and to use. The university created visual versions of the motors’ service manuals with easy-to-follow illustrations for using and servicing the motors.

“We noticed right away that the women were more open to innovation. They also seemed to be more careful with the motors.”

Gordon Wilmsmeier, Professor of logistics at the University of Bogotá

The piangua harvesters, mostly women, were the first to adopt the new technology. “We noticed right away that the women were more open to innovation. They also seemed to be more careful with the motors,” says Sorge. Also, women in the region are harder hit by poverty and instability, which made them more willing to try something new.

The piangua is a key ingredient in Colombian cooking but is rarely consumed by the people of Guapi. Instead, they sell the molluscs to traders who sell them outside of the country, mostly to Ecuador. Ecuador’s piangua populations were decimated when their mangrove forests were converted into shrimp farms.

It takes around four hours of probing the slimy floor of the mangrove forest by hand to collect 100 cockles. That’s enough to earn the equivalent of €5 from the exporters. But the women had been paying four euros a day for the gasoline for their boats. Today, 25 women who harvest the shellfish for a living share the four electric motors.

Electric motors are a novelty in the mangrove swamps – the locals instantly understood how to operate and enjoy the technology.

The new electric motors boosted their earnings by 40 per cent, Wilmsmeier says. If the women earn more, they don’t need to harvest as many cockles, which protects the species from overharvesting. It’s a win-win situation.

New recipes for a new life

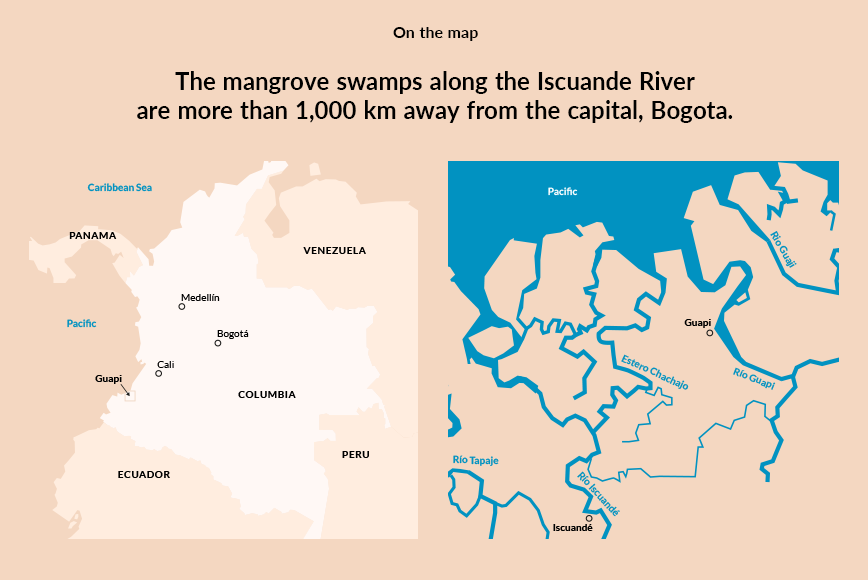

The piangua harvesters and the researchers are also trying to find new buyers, so more of the profits can stay in the community. Top Colombian chefs may be the ideal target audience. Leonor Espinosa, or “Leo” as she is affectionately called, is lending a hand. She is the country’s most famous chef and recently organized an event for cooks where she presented her own cockle creations and discussed seafood quality. Now, Bogotá’s best cooks want live piangua, and they want big ones. Wilmsmeier and Sorge are already in contact with a startup that specializes in sustainable logistics to have the shellfish transported from the swamplands to the capital around 1,000 km away.

This may establish a transport route for crabs, catfish, and bass as well. Seeing the women’s success, the men in the villages around Guapi are interested as well. They asked Wilmsmeier and Sorge a critical question: Can the electric motors pull heavy, 800-metre long nets? On their most recent visit, the researchers put a Torqeedo Cruise motor on a fishing boat, set out on the wide Iscuande River and proved to the fisherman that it’s no problem at all.

The Colombian project proves if we work in cooperation with nature, we can keep enjoying the bounty it provides.

A visit from the ambassador

“It’s amazing how everything worked out,” says Wilmsmeier. Besides Leonor Espinosa, the popular Colombian bands Systema Solar and Bomba Estério are also on board, helping to raise awareness. When Wilmsmeier and Sorge went to Berlin to talk about Inno Piangua, they were greeted by the Colombian ambassador to Germany who promised to support the project. Things are progressing. Of course, four electric motors don’t make up for the thousands of gasoline engines buzzing around the mangrove swamps. But you have to start somewhere. In February, solar panel implementation began in the region. Torqeedo developed a custom charging prototype for the application and donated the solar panels for the Cruise and Travel motors. Currently, the motors are in daily use and powered with clean, unlimited renewable energy. And the use of green energy naturally also increases the fisherwomen's profits.

Wilmsmeier and Sorge are thinking even bigger: they dream of fossil fuel-free national parks and new ways to fish sustainably and without generating CO2 emissions. Iscuande showed them it’s possible, and the Colombian fisheries association has opened a department for marine electric mobility. As Wilmsmeier points out, “We want to show how open and modern people can be in regions that are often forgotten. One day, the so-called developing world may very well surpass industrial nations in the adoption of electric transportation.”

Infobox

The international Inno Piangua project seeks to improve the quality of life for the fishers of Colombia’s Narino region without destroying the environment.

Electric mobility and renewable energy are an essential part of the initiative. Torqeedo has supported the project by donating five motors.

For more information, visit the › HTW Berlin Website

More information:

Find high-resolution pictures at the: › Torqeedo Dropbox

Find the main catalogue 2020 here: › Catalogue 2020

Relevant Torqeedo Products

A new way to lift all boats

- Commerce

- Vision

- Bateaux motorisés

- Communiqués de presse